Jacob Stratman, whose poem “For the Amaryllis belladonna who dares to bloom on this mid-August morning in Arkansas” appears in SRPR Issue 46.1, reflects on stillness, hope, beauty, and pantoums.

What I appreciate most about the formal qualities of the pantoum is that, through its repeating lines, it resists forward movement. It’s not able to narrate very well because the form invites its content to be still—to rest in itself, even uncomfortably, but possibly (hopefully) waiting for some sort of truth to reveal itself. Harold Schweizer, in his book On Waiting, reminds us that

In waiting, the waiter thus feels—impatiently—his own being; it is a feeling of the un-measurable, perhaps the immeasurable, that which cannot be protracted or contracted . . . There is no escape from it. The waiter waits in the time that he is, willy-nilly. He waits, he vacillates, he wills it—he wills it not, he paces, he looks at his watch. His pacing performs the conflict implied in his impatience (17)

It’s this kind of waiting—this stillness—that is present in the pantoum that is pretty perfect for a pandemic—for a shutdown when none of us feel like we’re moving forward at all; where everything repeats itself and sits in on itself; where we learn how to wait.

During the spring and summer months of 2020, I spent a lot of time walking around Sager Creek, a small part of the Illinois watershed in Northwest Arkansas—my home for the last 14 years. Here, within walking distance from where we live, my youngest son and I would look for crawdads under slate rock, avoid cottonmouths sunning on the paths, fish for smallmouth bass and bluegills, admire the blue heron who always seemed to be right around the bend, wander through hidden parts of the creek, and then wake up and do it again the next day.

The poem graciously included in SRPR, “For the Amaryllis belladonna who dares to bloom on this mid-August morning in Arkansas,” is a pantoum, yes, and a nod to standing still in one place for months—especially when only one thing, or one aspect of a thing, dominates and influences how you see the whole world; however, the title, at the same time the poem leans toward despair, wants you to feel the pull of the ode—a celebration of blooming and beauty in the middle of stagnation and stillness. The Amaryllis belladonna, or at least the type I see here in the summer, only blooms in August, when everything else is starting to fade, dry up, and/or die: grass, creek water, the green on the trees, and even the cicadas. These flowers have a long, thin stem with spreading, delicate pink petals. I’ve always heard them called “naked ladies.” Each late summer, someone will remark about the surprise and beauty of the naked ladies around town.

Whether I pull it off or not is up to you, of course, but the poem attempts to explore a tension, in this particular place and time, between the difficulty of waiting—of sitting still in our own perceptions—and hoping for the beauty that still blooms all around us.

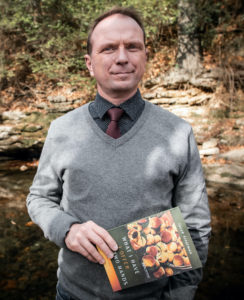

Jacob Stratman’s first book of poems, “What I have I Offer With Two Hands,” is a part of the Poiema Poetry Series (Cascade, 2019). New poems can be found in Moria, Amethyst, 2River, Ekstasis, and others. He teaches at John Brown University in Siloam Springs, AR.

You can order a physical copy of 46.1 on our website, or purchase a 2-year subscription.

And if you want to keep up with us on social media, you can follow us across

Instagram: @srpr_news

Twitter: @srpr_news

Facebook: SRPR (Spoon River Poetry Review)